I got some advice in my younger years that has worked very well for me since and no doubt will continue to be valuable for many years to come.

That advice was from a (then) well-known actor. In an interview he was asked about stage fright and what he did to get over it. His answer was to just pretend (act) like someone with confidence.

I took that bit of wisdom and ran with it.

I was in junior high school at the time and starting to make a name for myself. I was gaining popularity, but I had one problem: I was terribly shy and bashful.

What to do?

It was during that time I heard the advice from that actor. I needed to act more confident around people.

So I did. I formed a kind of image in my head of coming off as smart, funny, approachable and fun to be around. I could do that, I thought. But I knew deep inside I would always be an introvert and still be living in my head.

But that advice led to me striking a balance between bashful and socially confident: I learned to be an extroverted introvert (called in psychological terms an ambivert).

It served me well; I made it through the rest of my school years and beyond with people thinking I was full of confidence. I have spent my life since then acting confidently, though I still kind of slip into bashful shyness sometimes.

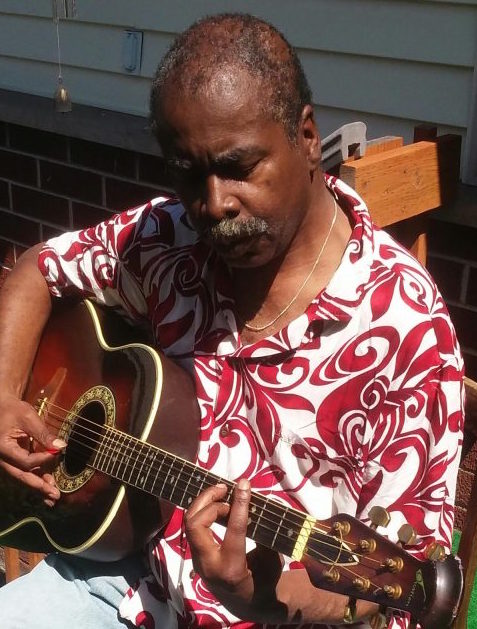

That acting was especially useful when I became a performing musician and later a professional journalist.

When I was just starting out, I covered a high profile political event. I looked around and saw camera crews from national media outlets. CNN, USA Today, CBS, NBC, and other outlets were all there. And here I was, just starting out, writing for a small, relatively unknown weekly newspaper in Minneapolis and St. Paul, had never studied journalism and had no real journalistic experience.

I felt very intimidated.

But I got a grip on myself. I looked around that huge room and told myself I was being silly; I was as good as anybody in that room. So I started acting like it, and a year later I won the first of several journalism awards, a national award, at that. Other awards and fellowships followed.

The same approach worked when I was playing guitar in bands.

I’ve followed the actor’s advice, in modified form most of my life: whatever it is you are trying to do or to be, think it and be it. I can tell you from decades of experience it works. But there are a couple of things to keep in mind. I’ll use confidence building as my example.

Probably the most important thing to remember about acting confidently is don’t overdo it; don’t overcompensate. Keep it realistic. Outwardly become the person that lives inside you—don’t try to be something you could never hope to be. You will probably never be president but that doesn’t mean you can’t run for city council or school board or something. Be confident but don’t become obnoxious or unbearable. (If you’re already that, learn how to act like someone without those traits).

That leads to two more concepts, both from psychology. They’re known as the Dunning-Kruger effect and impostor syndrome.

The Dunning-Kruger effect concerns how people rate their own competence. People with lower levels of competence often overestimate their competence, while highly competent people often underestimate theirs. This is where it’s advisable and a good idea to know yourself, to really know your strengths and weaknesses and to be realistic about what they are.

The impostor syndrome happens when someone reaches a certain level of achievement, but deep down fear that people will see right through them and see them as no-talent fakes. They may feel they had just been lucky and don’t really deserve what followed. These are people who don’t have clear vision of themselves or reality. Deep down you feel you aren’t the real thing, but other people only see the outward you. It’s like when I was playing guitar and made a mistake. I just kept playing; I didn’t act like I’d messed up and besides, I knew what it was supposed to sound like, the audience didn’t, so it was only a big deal if I acted like I’d messed up. I believe the impostor syndrome is behind the deaths or declines of some pretty good musicians and actors.

There’s more, but I don’t have any doubt you will put the pieces together.

One way, still using confidence as an example, is to get past that feeling of helplessness or uselessness so many traumatic brain injury survivors feel. See yourself helping someone do something, then act like someone with something useful to offer. As they say in the self-help books, think it and be it.

Here’s an example from my personal recovery from a stroke.

When I was discharged from the hospital I was required to leave with a walker. I was considered (by hospital staff) to be a high fall risk. I’ve never used the walker. My dear friend and caregiver, Nancy and I went round and round about me using the walker, Nancy urging me to use it and me refusing to. I was completely confident I would not fall and I have never fallen. Relying only on myself got me far beyond the point where anyone thinks I need a walker faster than I would have gotten there without the confidence that I could do it.

Projecting confidence may help get past the social isolation survivors feel. I believe some of what’s going on in that case is the people you knew before your injury don’t know how to interact with the new you, and so withdraw. I’m wondering whether sometimes that can be a reaction to the way you are acting. If you see yourself being confident in social settings you can make it easier to be accepted. Be confident that, for example, if you let others know what you are going through and how your brain injury makes you feel, you can help that person feel more comfortable. Confidence attracts people; awkwardness and self-consciousness less so.

There’s nothing much wrong with still feeling a tad uncomfortable; keep in mind people don’t have access to your inner self, but they will respond to what you project outwardly. I remain at heart a shy and bashful man, but that would likely be news to people who’ve known me over these years.

I hope you will try what I’ve tried here to explain. And I hope you will contact me and let me know how you are doing with it.

I’m confident you can do it.

| Isaac Peterson grew up on an Air Force base near Cheyenne, Wyoming. After graduating from the University of Wyoming, he embarked on a career as an award-winning investigative journalist and as a semi-professional musician in the Twin Cities, the place he called home on and off for 35 years. He doesn’t mind it at all if someone offers to pick up his restaurant tab and, also, welcomes reader comments. Email him at isaac3rd@gmail.com. Read more articles by Isaac here; https://www.brainenergysupportteam.org/archives/tag/isaac-peterson |

|---|