According to the American Kennel Club, more than 80 million people with disabilities use service dogs.

The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) classifies a service dog as a dog that is individually trained to do work or perform tasks for a person with a disability and goes on to say that service dogs can help people with disabilities live healthier, happier, and less stressful lives.

So how does a service dog do all that?

I couldn’t answer that all on my own, so I talked to Molly Neher, Director of Operations and Programs at Atlas Assistance Dogs, a national group that helps people with disabilities train their service dogs. Molly is also a brain injury survivor and has epilepsy.

Everything you’re about to read came from talking to her.

One of the first things to know is that service dogs are different from comfort or emotional support animals.

Comfort and emotional support animals play important roles in a disabled person’s life but don’t require training for specific tasks the way service dogs do; just their presence provides comfort and reassurance. There are also restrictions on emotional support and comfort animals being in public spaces that don’t apply to service dogs.

The Americans With Disabilities Act makes allowances for service dogs to be with their owner or handler in most public spaces, like stores, buses, trains and airplanes. They are required to be trained for at least one task that directly relates to their handler’s disability.

It’s not necessary for service dogs to be any specific breed, although German shepherds, golden retrievers and Labrador retrievers are commonly used. The temperament of the dog is key.

Service dogs can’t show signs of aggression, fear or anxiety. They do need to show signs of motivation to work. They must also be a match with the work they’re going to do for their owner. An example Molly gave involved dogs doing mobility work. In that case, it can’t be a small dog like a chihuahua. On the other hand a small dog might be ideal for someone who needs a dog sensitive to conditions like diabetes, who can be trained to know what their particular handler needs.

Regardless of the service dog’s assignment(s) or breed, Molly made it clear on how she and her organization train service dogs for their work.

“We only use positive reinforcement training. We focus on physical training of the dog and the person but we don’t use any aversive training, no fear training, so we only use positive, ethical methods.”

Another thing Molly emphasized is the need to understand that having a service dog isn’t a miracle cure for people with disabilities.

Using seizures as an example, she said, “A lot of people think that all dogs can just naturally alert a person with seizures of an oncoming seizure; some dogs can do that, but the science behind dogs doing that is a little unclear.”

Molly continues, “But what we do is train dogs how we want them to help during the seizure, so we really don’t guarantee the dog is going to learn how to alert them to the seizure beforehand. There’s the hope that they will be able to tell what is about to happen, but we can’t guarantee that. There are ways that a dog can help during a seizure and give someone a lot more independence. But we shouldn’t expect that a service dog is just going to alert someone to seizures before they happen.”

Molly described how her own service dog, a labradoodle named Reid, has helped her through her brain injury and epileptic seizures.

“Reid is trained to know when I’m having a seizure, to lay right next to me. He keeps me safe. He makes sure that I’m not injuring myself if I’m having a lot of movement. He’ll place himself in certain ways, on top of me and next to me so my arms and legs aren’t going to move in a way that’s going to hurt me.

And then after a seizure he knows to start moving my arms and legs when I’m ready to get up. But if I’m not really ready to get up yet, he will stay laying on top of me until he feels that I’m actually safe. And when I am ready, one of the things he does that is really helpful is he stands and I can put my hands on his shoulders, put all my weight on him and get up just bracing on his back, which is major for me because it means I don’t have to rely on other people to help me stand up. Which is really big for my independence in not needing other people to help me up or move me in ways that I’m not comfortable with.”

Every dog/owner team is going to interact differently and they’re going to form their own unique bond and their own individual relationship. Each team is going to work and train together a little differently and have their own kind of communication. The owner and the service dog make a commitment to each other, an ongoing, lifelong commitment.

“It’s a lot of work to work with your dog and train your dog, especially for someone with a brain injury where they experience fatigue and difficulty focusing, or a whole wide variety of symptoms that can really take extra energy and extra work. It’s not just that a service dog comes into your life and everything is fixed. It takes an emotional toll as well if you’re training the dog and you have to be ready for that,” Molly says.

Molly adds, “But just having that presence, knowing the dog is going to be there for you. Without my dog I wouldn’t have been able to finish college. I wouldn’t have a job today. I would probably still be living with my parents and laying in bed. Service dogs can quite literally save lives.”

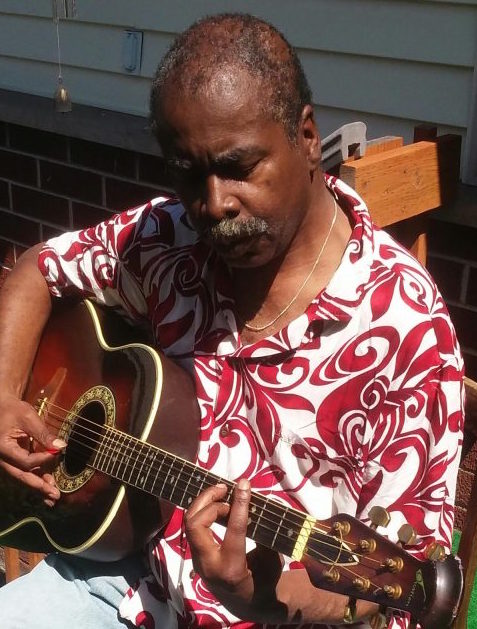

| Isaac Peterson grew up on an Air Force base near Cheyenne, Wyoming. After graduating from the University of Wyoming, he embarked on a career as an award-winning investigative journalist and as a semi-professional musician in the Twin Cities, the place he called home on and off for 35 years. He doesn’t mind it at all if someone offers to pick up his restaurant tab and, also, welcomes reader comments. Email him at isaac3rd@gmail.com. Read more articles by Isaac here; https://www.brainenergysupportteam.org/archives/tag/isaac-peterson |

|---|