Editor’s note: The Brain Energy Support Team (BEST) is pleased to introduce writer, musician, instructor, stroke survivor and stroke awareness advocate, Andy Dovey, as our newest BEST guest blogger. Welcome, Andy!–KT

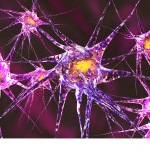

As you may be aware, there is a great deal of talk about neuroplasticity. This is defined as the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections, not just when we’re young, but also throughout all our lives. So, the more often you perform an action or behave a certain way, the more it gets physically wired into your brain.

As you may be aware, there is a great deal of talk about neuroplasticity. This is defined as the brain’s ability to reorganize itself by forming new neural connections, not just when we’re young, but also throughout all our lives. So, the more often you perform an action or behave a certain way, the more it gets physically wired into your brain.

Of course, this can be positive, but it can also be negative. We can learn things correctly and get into good habits, but also the opposite. Your repeated mental states, responses, and behaviors become neural traits.

Neuroplasticity allows the neurons (nerve cells) in the brain to adjust themselves in response to new situations or to changes in their environment. I prefer to call this learning. I think that’s something we can all understand and relate to! So, us traumatic brain injury (TBI) and acquired brain injury (ABI) survivors have some degree of brain damage, so does this mean we can learn? Or in many cases, re-learn?

When I was in hospital, unable to grip much with my left hand, I thought (naturally enough) that the problem was with my hand. But the problem was really with my brain. The electrical impulses generated by my brain that sent signals to the muscles in my hand weren’t getting through. Possibly those electrical signals weren’t even being generated. My stroke, my brain attack, had damaged part of my brain and these signals were scrambled, interrupted or maybe just not firing. The net result – spasticity in my hand.

I also had balance issues. I couldn’t stand up without swaying around like a tree in a hurricane and I couldn’t walk unaided. This wasn’t due to my muscles suddenly becoming weak and uncoordinated overnight. I hadn’t suddenly suffered instantaneous muscle wastage. No, this was due to brain damage. I was unable to get the correct signals from my brain to my limbs and muscles at the correct time and in the correct sequence in order to stay upright and walk. My limbs and muscles were fine, my brain was not.

As an aside, we see similar issues with sufferers of Parkinson’s Disease. Medication tries to re-balance chemicals in the brain (mainly dopamine), and recent advances in technology have resulted in surgery to implant micro-electrodes in the brain to enable deep brain stimulation in order to attempt to alleviate some of the more severe symptoms of the motor systems (shaking, etc).

So, five years later, how come I can now walk once more (albeit with a stick)? And I can grip once more with my left hand? (And other things that I won’t bore you with, for now)! Well, if you think about a toddler who is learning to walk, it takes time, practice and lots of repetition before the wobbly, stumbling toddler can walk and run with good balance and coordination. What’s happening in this time is that the toddler’s brain is learning to trigger the correct electrical signals at the correct time and in the correct way in order to stimulate the correct muscles to do their job, in a beautifully coordinated piece of bio-engineering. The toddler’s brain is being hard wired to perform this task. We call it learning. It does this so many times that the neurons in the brain (and central nervous system) generate connections (synapses) that become information super highways and are so super-efficient at what they do that we don’t even think about it. We just walk. Or run. Or play tennis, or golf, or the piano, or juggle, or whatever.

As I know from my own experience, when you have to now really think about walking, making every movement a conscious exercise (because those information super highways have been damaged and disrupted), it is not only extremely difficult, but also very tiring as the brain is working overtime to re-route those signals and build new super highways.

In the early days of my physiotherapy, I remember being asked to walk and then look to one side when told to do so by the physiotherapist. How hard can that be, right? I lurched forwards (I wouldn’t call it walking) and the physio said, look left and as I did, so I crashed into the wall on my left. Just fell over. It was just too much for my brain to cope with. I can now look around as I’m walking (to a degree) but it makes me very unsteady, so I have learnt (that word again) to stop walking, steady myself and then look around. It’s still a very conscious exercise, but now much safer!

My point is that we can relearn things but that (in this case) relearning is NOT a short cut and is, in effect, the same as learning for the very first time. It’s just that (unlike the toddler) we can remember we used to walk OK and expect to be able to do it again fairly quickly and easily. So, whatever your brain trauma deficits are, try and look upon them as learning opportunities. Say to yourself, if I had to learn this thing (whatever it is) from scratch, how long would it take me and how many times would I have to do it in order to be proficient. And remember that your estimations will be based on prior experience when your brain was operating at 100 percent. It isn’t now, so the learning will take much longer and will be very draining due to your reduced brain processing power.

Take care everyone, and thanks for reading my blog from Scotland!

Andy

About Andy: On May 28 2013, Andy was struck down by an ischemic cerebellar stroke. He developed complications and two days later underwent emergency brain surgery to decompress his skull due to hydrocephalus. He almost died and has five missing days of which he has no memory of whatsoever. Prior to his brain attack, Andy was a professional musician, a drummer, and earned his living both as a player and teacher. He has been unable to return to work but is writing a CD of music inspired by his stroke story in order to raise awareness of stroke, particularly among younger people. As fellow brain injury survivors will understand, work is progressing at a snail’s pace! This project will also raise funds for the charity Different Strokes. Please visit www.brainattackmusic.com to read more and to listen to some demo tracks. Andy lives with his wife in the beautiful Scottish Borders, very close to where the River Teviot meets the world famous River Tweed and has two sons, a stepson and stepdaughter, all of whom have flown the nest and are making their own way in life. As well as a deep love of all types of music, Andy enjoys watching sport, reading about history, learning about the brain and enjoying the peace and calm of the Scottish countryside.